-

Last updated on

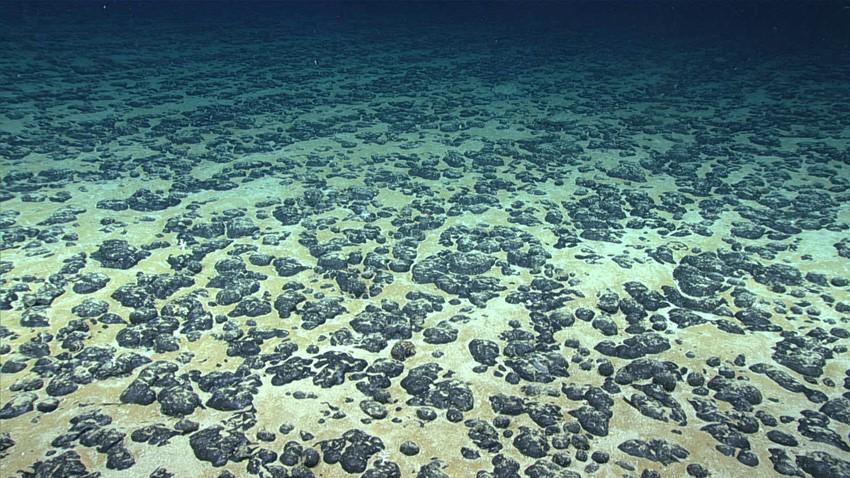

A patch of seabed richly strewn with manganese nodules. © NOAA Ocean Exploration

Seabed mining is the subject of hot debate. Given that Belgium is a member of the Council of the International Seabed Authority in 2023, our country can play an active role in the drafting of a legal framework for the mining of mineral resources on the seabed in international waters. Find out all there is to know through 11 questions.

1. What is the International Seabed Authority?

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is a specialised UN Agency acting as an autonomous intergovernmental organisation based in Kingston, Jamaica.

Alongside the European Union, 167 countries form part of the ISA. These are the same 'contracting parties' who ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (see below). UNCLOS provides the unique legal framework for all activities at sea.

The meeting room of the ISA. © ISA

2. What does the International Seabed Authority do?

The ISA originated within the framework of UNCLOS, the negotiations of which were finalised in 1982. The Convention entered into force in 1994. It states that the ISA is 'the ultimate authority through which the parties shall organise and control activities in 'the Area' for the purpose of managing resources within the Area.'

The Area refers to the seabed and its subsoil in international waters, namely those parts of the oceans that are beyond any national jurisdiction. It constitutes a common heritage of humanity.

Coastal States do have sovereign rights, including the right to economic exploitation within their own maritime zone. It consists of the territorial sea, the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf. In the territorial sea - up to 12 nautical miles from the baseline - Member States have full sovereignty. In the Exclusive Economic Zone - up to 200 nautical miles from the baseline - and even on the Continental Shelf - possibly beyond 200 miles - those rights are more focused on economic exploitation. The figure below shows the various zones at sea.

In other words, only the ISA is authorised to regulate all activities related to the Area, including possible mineral extraction. No individual country has the right to commandeer the Area or its resources.

3. What are the main bodies of the International Seabed Authority?

The Council has 36 members elected by the Assembly (see below). It draws up the rules and procedures to be approved by the Assembly. It also approves contracts with countries and private companies for the purposes of prospecting, exploration and, in the future, seabed mining.

The Assembly is where all 167 Member States sit, next to the European Union. It approves regulations and elects members of the Council and other bodies, including the Secretary General.

The Secretariat is responsible for the management and organisation of the ISA and is headed by the Secretary General.

A total of 41 experts sit on the Legal and Technical Commission (LTC) for a five-year term. The Council elects members from candidates nominated by Member States. Among other things, the LTC oversees seabed exploration, and formulates and revises regulations.

4. What is Belgium's task within the ISA?

Belgium has been a member of the ISA since its inception and thus sits on the Assembly. Any member of the Assembly may also participate in Council meetings as an observer.

Our country has, since ISA's establishment in 1994, also been a member of the Council 4 times, the last time in 2016.

In 2023, Belgium will again be a member of the Council. This was not without its challenges. The mandate was preceded by extensive negotiations conducted by our country, even up to the level of our Minister of Foreign Affairs, with the support of our embassy in Kingston - which is also the Permanent Representation to ISA - and the network of diplomatic missions, in consultation with the FPS Economy and the FPS Public Health (marine environmental policy division).

As a pioneer of the Blue Leaders - these are countries pushing for far-reaching protection of the oceans (30% by 2030) - Belgium will act within the Council as an active campaigner of very strict regulations.

Belgian marine biologist Ellen Pape sits on the Legal and Technical Commission from January 2023 to December 2027. It is the first time a Belgian scientist has been a member of this commission.

Our ambassador in Kingston, Hugo Verbist (centre), represents Belgium in the ISA. At left, staff member Joost Depaepe. © ISA

5. Why is the seabed so important?

The much-needed green energy transition - including solar and wind energy and the use of electric cars - and digitisation require huge amounts of minerals. Now the seabed appears to be extremely rich in metal-rich nodules. Best known are the polymetallic or manganese nodules that contain a lot of manganese and, to a lesser extent, metals such as nickel, cobalt and copper. In addition, there are polymetallic sulphides (mainly copper and zinc, also lead, gold and silver) and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts (like manganese nodules but with more cobalt, platinum and rare earth metals).

At the same time, the oceans - and their soils - are of critical importance to climate and environment. They absorb, for example, massive amounts of carbon and heat. They are also home to immense biodiversity. Early March 2023, the United Nations (UN) concluded negotiations to enable the protection of marine zones in international waters. This agreement is supposed to be signed some time this year and subsequently ratified.

So the possible mining of the seabed is an extremely delicate issue. Most NGOs are calling for a moratorium. Belgium is not advocating a moratorium, but believes that one of the things that is necessary is to have a regulatory framework in place beforehand, one that protects the marine environment from potentially harmful effects of seabed mining (or deep-sea mining).

A typical manganese nodule. © iStock

6. How far has the ISA got with its regulations?

The regulations surrounding prospecting and exploration were finalised a long time ago. Companies can conduct limited exploration activities in the Area provided they are sponsored by an ISA Member State. The sponsoring country does not provide financial support but does act as a guarantor for the company. In case of damage during exploration, then it is up to the sponsoring State to deal with it.

The regulations surrounding exploitation, on the other hand, are far from complete. After all, it is not easy to work out sound regulations that every party can get behind.

The island of Nauru has invoked a specific legal provision that gives ISA Member States 2 years to finalise regulations. This term expires on 9 July 2023. By then the regulations must be finished, because after that date a work plan for exploitation could already be submitted. Nauru sponsors the company Nauru Ocean Resources Company Inc. (NORI), subsidiary of Canada's The Metals Company.

That the 9 July deadline will be met to adopt the full regulations around exploitation is all but ruled out. Most countries feel that this deadline is too short and goes against the precautionary principle. Neither do they accept that exploitation is started before adequate regulations are in place. Some countries also propose a pause or moratorium.

7. What position will Belgium defend?

Belgium strictly applies the precautionary principle. There can be no exploitation of the seabed without an agreement on a set of rules and regulations that prevent significant damage to ocean biodiversity and marine ecosystems.

As far as Belgium is concerned, three conditions must be met:

- The ISA must adopt robust, environmentally friendly rules, regulations and procedures. That regulatory framework should lead to "the highest and most effective level of protection of the marine environment - including fragile ecosystems and the global climate functions of the oceans - from the potentially harmful effects of deep-sea exploitation, both in the short and long term". That leaves no room for artificial deadlines for the (rushed) completion of regulations.

- There is a need for 'more independent scientific research to provide sufficient and appropriate information to make informed, evidence-based decisions about the environmental impact of operations'.

- It is impossible to embark on exploitation without also considering the protection of the ocean. For Belgium, it is crystal clear that '30% of the oceans must be qualitatively protected before we can approve a work plan for exploitation'.

Any mining activity must be deferred until all of the above conditions are met.

8. What results can we expect in 2023?

Belgium hopes that the regulations can be drafted in a more structured and efficient manner than has been the case so far.

Moreover, after the deadline of 9 July 2023, legal uncertainty should be avoided if a work plan for exploitation were to be submitted. To avoid such a scenario, our country, together with Singapore, organised an 'intersessional dialogue' on 8 March 2023, to get the Member States and observers to sing from the same hymn sheet. Belgium and Singapore reported to the Council on this dialogue in mid-March, and negotiations are underway for a Council decision on this very issue.

9. Where are explorations already happening? And what do those teach us?

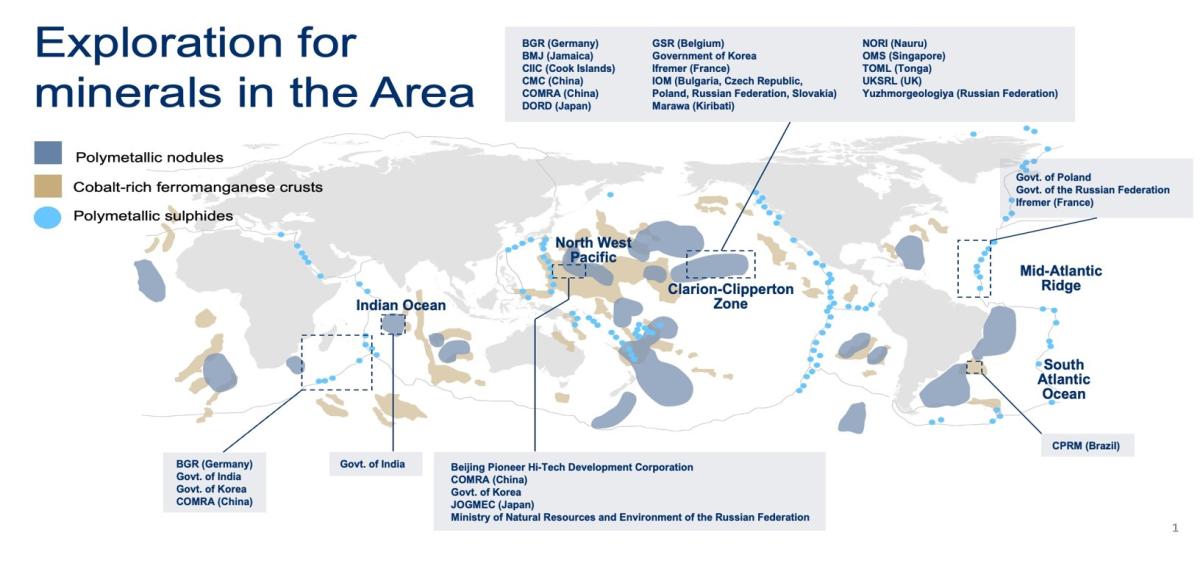

Some 30 contractors are currently exploring the seabed (see world map). Sponsoring countries, in addition to Belgium, are China, Germany, France, Singapore, Japan and India.

To date, no unanimous conclusions can be drawn from the study. Some contractors argue that the necessary research is underway while NGOs feel that too much essential knowledge about the deep sea is still lacking. Exploration is necessary anyway as the impetus for possible exploitation in the future. It teaches us whether the companies are ready for it and whether there are harmful effects on the environment.

Overview of current exploration zones and the presence of metal-rich nodules. © ISA

10. Belgium is sponsoring exploration through GSR, a subsidiary of DEME. NGOs are critical of this. What exactly is going on?

Exploration is effectively underway, and NGOs fear it will lead to exploitation. For now, there is no question of that. No decision has yet been made by Belgium to later sponsor GSR for exploitation.

Belgium is currently drafting national legislation around deep-sea mining. It is set to formulate the conditions that will apply if Belgium were to express the wish to sponsor the exploitation of a company at some point in the future. Incidentally, sponsorship in this context means overseeing the implementation of regulations, it is not about financially backing the company. The bill is expected to be submitted to the House of Representatives by the summer.

11. When could comprehensive regulations be ready?

Belgium is of the opinion that it is preferable not to put a deadline on that. What we need are efficient negotiations leading to sound regulations in which all the conditions mentioned above are met. This should not happen under the pressure of artificial deadlines. Even though we do want to make progress.

More on Planet

Protecting mangroves secures future of fishermen

The Belgian NGO, Louvain Coopération, is replanting vanished mangroves in Madagascar. These tidal forests play a crucial role in...

An unexpectedly ambitious UN biodiversity framework

Protect 30% of all land and oceans by 2030 and $700 billion a year for biodiversity. The new UN biodiversity framework can be ca...

Sahel youth at COP27: "We are the future and the future rests on our shoulders"

At the invitation of Belgium, 8 young people from Senegal, Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali were able to participate in the recent c...