-

Last updated on

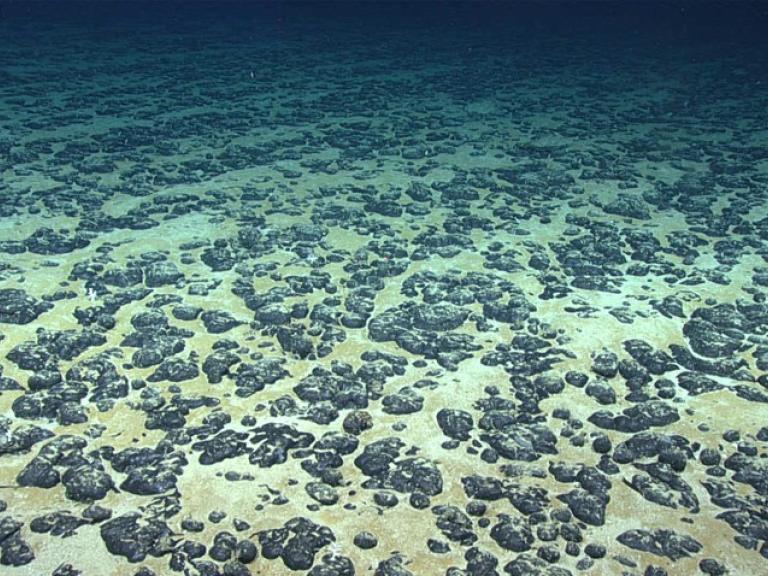

Our oceans harbour a gigantic biodiversity and are of utmost importance for our planet. © iStock

On 4 March 2023, the UN settled on an agreement enabling the protection of biodiversity in the high seas. Our FPS took an active part in the negotiations.

Earlier, we reported that the United Nations (UN) had hammered out an unexpectedly ambitious biodiversity framework. At least 30% of all land and oceans should be protected by 2030. That 30% is of importance because it's the point at which you reach a turning point to keep the other 70% liveable as well.

Urgent need for a high seas agreement

But that was not the end of the matter, and certainly not as far as the oceans are concerned. Until then, an agreement providing a binding legal framework for the protection of biodiversity on the high seas was still lacking.

Indeed, those high seas enjoy a special legal status. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) states that no individual country can claim rights over those high seas. In other words, the high seas are beyond any national jurisdiction. In jargon, therefore, we refer to an agreement on the Marine Biodiversity Of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ).

To be clear, the term “high seas” refers to the surface and the water column of the seas beyond the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and territorial waters. In the latter zones, coastal states can assert some (EEZ) or all (territorial waters) rights (see figure). The high seas cover a huge area. They occupy just over half the planet and over 60% of the oceans.

A long drawn-out process since 2006

The UN has been working on it since 2006. Actual negotiations began in 2017. These have always been open to all UN Member States, even those that have not ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. But because so many countries subscribe to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, it has become common law.

Points of contention included so-called 'marine genetic resources'. The high seas harbour a gigantic biodiversity that could have applications in medicine and nutrition, among others. This could have economic benefits. Poorer countries strongly urged that those benefits be shared fairly. They also felt that they should have sufficient access to the knowledge about the high seas. The wording of the regulations in the event of disputes also took a lot of time and effort.

A framework to protect natural areas on the high seas

On 4 March 2023, the UN was finally able to conclude negotiations on the text of the BBNJ Agreement. It outlines the framework by which biodiversity in areas of the high seas could be protected in the future. This can range from complete protection (no human activity possible) to strict regulation of human activities. For example, through contained fishing, sustainable shipping, scientific research with respect for nature and sustainable water tourism.

The agreement further states that the environmental impact of human activities on the high seas must be rigorously assessed.

To implement the agreement, poorer countries' technical capabilities will be strengthened and marine technology transferred. Its terms will be further elaborated by the upcoming 'conferences of the parties' (COPs).

Crucial next steps

Although a first very important step was taken, the agreement is not yet legally valid today. Technical proofreading (punctuation, numbering and so on) as well as translations from English into the UN's other official working languages, notably French, Spanish, Chinese, Arabic and Russian, are currently under way. The official adoption should take place in the month of June.

Thereafter, all countries that declare themselves parties will sign the agreement. This should take place in autumn, possibly during the week of the UN General Assembly or a little later. Note that a signature is only a declaration of intent, at that point the agreement does not yet have any legal effect. It does not truly enter into force until at least 60 parties have ratified the agreement. A signed agreement must be approved by parliamentary assent before the instrument of ratification can be deposited.

The ratification process could drag on for at least a year. After the agreement enters into force, the first COP will be organised within the year of its entry into force. Additional COPs will take place regularly thereafter. Purpose: To detail the major principles contained in the agreement. The very first COP (COP1) is unlikely to take place before 2025.

Belgium made a major contribution to the success of the BBNJ Agreement

Belgium has been actively working towards the success of the BBNJ Agreement. Indeed, in 2019, our country was one of the founding members of the Blue Leaders, a group of countries working towards qualitative protection of 30% of the oceans by 2030 and an ambitious BBNJ Agreement. Thus, our country, together with other countries and organisers, organised several online dialogues during the COVID-19 period in order to ensure that attention to the negotiations about BBNJ would not wane.

Belgium also secured most of its key requirements. Among other things, the plan for far-reaching protection of the high seas. The Agreement also states that consensus should always be sought and only if that proves impossible, at least a “qualified majority" is needed. That is a large majority, certainly more than 50% + 1. The qualified majority requirement should encourage parties to seek consensus anyway.

Belgium also wanted an independent secretariat for the agreement, and it will effectively get one. A separate secretariat with its own budget entails autonomy and clout. A campaign on the location of this future secretariat will take place during which Belgium will defend the candidacy of Brussels to house that secretariat.

In short, Belgium proved itself an active and assertive negotiator with great experience in finding compromise. We also deliberately chose those points that were worth fighting for. All this, of course, within the EU constellation.

Several agencies participated in the negotiations. Our FPS coordinated the Belgian position and focused especially on the more transversal aspects during the negotiations. For instance, finance and the legal aspects of disputes. The Marine Environment Service and the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences took on the more technical aspects related to the environment and marine biology.

As many countries as possible should ratify

Our country will continue its strong commitment to the oceans as a Blue Leader in the future. A first crucial step we want to push for is (rapid) ratification by as many State Parties as possible. Because the more countries that ratify the Agreement, the more weight it can carry, including for those countries that have not ratified it.

Ideally, the BBNJ Agreement should follow in the footsteps of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. That, thanks to its 167 State Parties (plus the European Union) - out of a total of some 193 UN Member States - also sets the most rules for non-parties. For example, if only 62 countries ratify the BBNJ Agreement, its regulations can hardly set the tone around the world. At present, 150 countries have agreed to the BBNJ Agreement, broad ratification should be possible.

The EU is already committing €40 million to support other countries in ratifying and implementing the agreement. Over 100 million euros is already available worldwide for this purpose. During the Belgian EU presidency (first half of 2024), our country will undertake efforts to encourage the ratification process. Later, we will also aim to establish the first natural area on the high seas as soon as possible.

The seabed falls under the ISA

To be clear, the BBNJ Agreement refers only to the high seas, that is, the surface and water column of international waters. The seabed and its subsoil within international waters are under the jurisdiction of the International Seabed Authority (ISA). Our country is a member of the ISA Council in 2023 and is also pushing for extremely strict regulation there to protect the seabed as much as possible. Belgium also demanded that 30% of the oceans must be qualitatively protected by 2030 before a work plan for exploitation can be approved.

More on Planet

Belgium funds biodiversity conference in the Congo Basin

For many years, Belgium has supported countries such as DR Congo in the implementation of their obligations that arise from the ...

Belgium helps decide on the seabed's fate - 11 QUESTIONS

Seabed mining is the subject of hot debate. Given that Belgium is a member of the Council of the International Seabed Authority ...

Protecting mangroves secures future of fishermen

The Belgian NGO, Louvain Coopération, is replanting vanished mangroves in Madagascar. These tidal forests play a crucial role in...