-

Last updated on

© Shutterstock

Summary

Trade is one of the key drivers of our country’s wealth and prosperity. Every year, the value of Belgian exports amounts to the equivalent of 80% of our GDP. As a small, open economy, Belgium has every interest in ensuring smooth international trade and investment flows. A dynamic trade policy that eliminates trade barriers, creates a level playing field for our firms, contributes to the green and digital transitions, and promotes universal values such as human rights is essential for Belgium. Some of our key trade policy objectives are:

- opening up external markets to foster growth and job creation at home and abroad;

- facilitating the creation and implementation of global trade rules;

- contributing to the green and digital transitions;

- integrating developing countries into the global trading system;

- supporting sustainable growth with respect for environmental and social standards.

Objectives for Belgium

The making of the EU’s trade policy

The Common Commercial Policy, or trade policy, is an exclusive competence of the European Union. To negotiate a trade deal with a third country, the European Commission needs the authorisation of the Council of the European Union in the form of directives, which are usually referred to as the mandate. The mandate provides the framework for the Commission to conduct its negotiations. The ministers of the Member States thus decide when to open negotiations and under what conditions. The Commission then conducts these negotiations in consultation with the Council’s Trade Policy Committee (TPC), in which the 27 EU Member States are represented. The Commission keeps the European Parliament immediately and fully informed, primarily through the Parliament’s International Trade Committee.

For Belgium, the Directorate-general European Affairs and Coordination (DGE) is charged with preparing, defining, coordinating, representing, defending and monitoring EU policy. The DGE prepares the Belgian decision-making process so that our country can speak with one voice and defend its interests in the Council of the EU. This is done on a weekly basis by consulting and coordinating with the competent federal and federated bodies. The DGE also assists the competent minister to clarify the coordinated Belgian position by responding to parliamentary questions. The DGE meets with experts, disseminates information to diplomatic posts, maintains bilateral contacts with the Commission and builds alliances with other like-minded European delegations.

Workflows

The EU approach to trade policy is multifaceted. First and foremost, the EU and Belgium pursue a multilateral approach seeking to negotiate and set global trade rules. This approach aims to maximise trade opportunities of our companies by ensuring a level playing field around the world, and also endeavours to integrate developing countries in the international trading system, a key concern for both Belgium and the EU.

The EU and Belgium are strongly committed to the effective functioning of the multilateral trading system based on the World Trade Organisation (WTO). For Belgium, it remains vital that the WTO can fulfil its three key roles by acting as a forum for trade negotiations, as a guardian of international trade rules, and as an arbitrator for trade disputes.

However, the WTO is in dire need of reform. For decades, the existence of international trade rules that many states agreed to and largely abided by, overseen by the WTO and enforced through an impartial dispute settlement system, has helped defuse trade tensions and prevent trade wars. Yet today, the WTO is struggling to adapt to (r)evolutions in international trade. Moreover, the WTO is hampered by rigid procedures and the conflicting interests of its members, while its role as a monitoring body is also jeopardised as its members fail to live up to transparency commitments. Since December 2019, the Appellate Body of the WTO dispute settlement mechanism has essentially been left paralysed. Although the EU has played a key role in the creation of an interim multiparty arbitration arrangement to safeguard the rights of the parties in ongoing and future disputes, a definitive solution remains elusive (for more information, see “Belgium’s horizontal, thematic priorities” below).

This quandary is further complicated by the unilateral measures that some countries have recently taken. Some of these actions are incompatible with WTO rules and have already prompted other countries to resort to countermeasures. These developments represent a major risk for the EU and Belgium: Both our imports and exports heavily rely on predictable, fair and rules-based international trade. Belgium therefore supports EU initiatives to reform the WTO in order to prepare it for the challenges of this century (including digitalisation, greening, sustainable development, etc.). Belgium, holding the rotating Presidency of the Council of the EU in the first half of 2024, will work with the European Commission and the other EU Member States to take the next step in this reform at the Thirteenth Ministerial Conference of the WTO.

As multilateral negotiations have stalled in recent years—particularly in the context of the WTO—the EU has adopted a pragmatic approach in its efforts to further promote international trade as a driving force behind growth and job creation. The Union also negotiates plurilateral agreements and is increasingly turning to regional and bilateral free trade agreements, an exception to the most-favoured nation principle that is explicitly accepted under the WTO rules.

Plurilateral trade agreements under the WTO include several members who share a common interest. In most cases, these agreements are the consequence of a failure to reach a multilateral agreement with all WTO members. Belgium particularly welcomes the progress made in the negotiations on digital trade (known as the E-commerce Joint Statement Initiative) and on investment facilitation (the Investment Facilitation for Development Joint Statement Initiative).

In addition to negotiations at the multilateral and plurilateral levels, the EU conducts various regional and bilateral trade negotiations. For example, the EU has recently concluded a raft of negotiations, leading to the entry into force of trade agreements with key partners such as Japan (2019), Singapore (2019), Vietnam (2020) and the United Kingdom (2021). Negotiations have also been completed with Chile and New Zealand, while negotiations are ongoing with Australia, India, Kenya, Indonesia, the Mercosur bloc, and Mexico, among others. More than a third of the EU’s international trade today takes place under preferential trade agreements.

During these regional and bilateral negotiations, Belgium actively advocates and defends its economic and strategic interests, such as significant tariff reductions and ambitious sustainable development provisions with a strong focus on climate and labour conditions, as well as compliance with EU sanitary and phytosanitary standards (SPS) and the protection of sensitive (agricultural) interests.

However, negotiations alone are not enough. These deals must also be implemented and the rules enforced. This is why the EU has the necessary trade defence instruments in place, such as anti-dumping, anti-subsidy and safeguard measures. Our country also supports the strengthening of autonomous legislative instruments aimed at creating a level playing field.

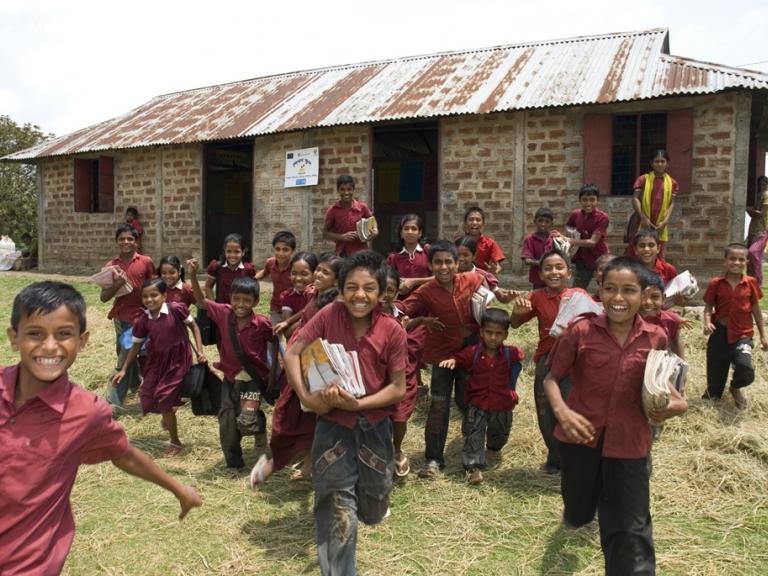

In its regional and bilateral negotiations with developing countries, the EU adopts an asymmetric approach, meaning that the EU provides benefits that it does not ask in return from these countries. This can for instance be done within the framework of Economic Partnership Agreements, or within the Generalised Scheme of Preferences, which is at the heart of the development dimension of EU trade policy. Under the rules of this scheme, the EU unilaterally offers preferential market access to developing countries (and even a near-total tariff exemption to least developed countries under the Everything But Arms initiative).

Horizontal, thematic priorities of Belgium

The Belgian trade agenda supports an open, sustainable and assertive policy that is in line with major EU policy developments, including the Green Deal.

Promoting sustainable development through trade policy is a key goal for our country. Ambitious and enforceable chapters on sustainable development are an essential part of trade agreements. Belgium seeks to further expand and strengthen these chapters in the negotiations of new agreements and draws particular attention to their effective implementation. Belgium also calls for the enhanced participation of civil society in mechanisms that monitor the implementation of these commitments (for instance through domestic advisory groups). The aim is to prevent trade from having any negative impact on sustainable development. Instead, trade policy should contribute to the protection of the environment and the respect for human rights and labour standards. The building blocks of this sustainable development approach can be summarised as follows:

- promoting the ratification and implementation of international instruments, in particular the core conventions of the International Labour Organisation, as well as multilateral environmental agreements, and biodiversity and climate agreements;

- ensuring the right to regulate, which recognises the right of each country to take the measures it deems necessary to achieve the objectives countries have agreed to in, for instance, environmental and labour conventions;

- introducing specific monitoring bodies in trade agreements, such as a committee to discuss the implementation of sustainable development commitments. This committee should maintain direct contacts with civil society (e.g. the domestic advisory groups established by various trade agreements). In line with Belgium’s support for civil society participation at the level of the EU and with the Union’s trading partners, the Directorate for Trade Policy also organises regular consultations with members of the Federal Council for Sustainable Development.

Belgium attaches importance not only to the negotiation of new trade agreements but also to the meticulous monitoring of trade agreements that have already entered into force. The European Commission’s annual reports on the implementation and enforcement of EU trade policy illustrate the concrete benefits of the agreements that are already in force. Since the provisional application of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) in 2017, for instance, Belgian exports to Canada have increased by 55%, reaching more than four billion euros in 2022. In 2022, more than one billion euros in import tariffs were saved by our partners in the purchase of Belgian products thanks to the trade agreements, testifying to their fundamental importance for the competitiveness of our companies. Proper monitoring also ensures that the commitments in agreements are correctly adhered to, including sustainability commitments, as discussed above.

Furthermore, Belgium and the EU are also continuing the ongoing process of reforming the rules that manage international investment protection. The EU has developed a new approach to settling investment disputes, known as the Investment Court System. This system is now incorporated in the EU’s bilateral trade agreements, including in CETA and in the investment protection agreements with Singapore and Vietnam. The Investment Court System aims to build a global coalition through trade agreements, with the objective of eventually setting up a multilateral investment court. Negotiations to create such a court are currently underway in the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (also known as UNCITRAL). The Commission consists of 30 members elected by the UN General Assembly for a six-year term. The goal of the EU and its Member States is to establish a permanent tribunal to settle investment disputes, which would be a radical departure from the current ad hoc arbitration system. As Belgium is currently a serving member of UNCITRAL until 2026, it will continue its efforts to support this multilateral reform project, including as host country of the seventh interim meeting of UNCITRAL’s Working Group III in 2024.

EU-AU summit: two unions, one vision

In Brussels, the European and African Union developed a hopeful plan for the future that should bring prosperity and stability t...

EU: more democracy in practice

Geography teacher Rafik Kiouah talks about his participation in a Belgian citizens' panel on a more democratic EU as part of the...

The EU joins forces for external action

The European Union is combining various funding channels into a single instrument: Global Europe. The simplification will give t...